Majorville Medicine Wheel a fun road trip

Last summer, while having dinner with friends Brook and Sylvia, we got chatting about Alberta road trips and the fun places we all have visited. Eventually, the conversation got to places that were increasingly more remote that we should visit. When Brook mentioned the Majorville Medicine Wheel (which I had never heard of, or these days don’t remember hearing about) that is only 2-hour drive from Calgary we all immediately said – Road Trip!

We made plans to go together in October, but poor weather resulting in us cancelling a couple of times and so then it was spring, but again bad weather meant we kept delaying our trip, until finally in the middle of August Mother Nature gave us a nice day to explore a remote area in the middle of Alberta’s southeastern grasslands.

The Majorville Medicine Wheel cairn is in the middle Alberta’s prairie grasslands. It doesn’t look like much but in fact it is one of the world’s most ancient sites.

Road Less Travelled

Much of the trip was along a dirt path.

We took highway #901 out of Calgary to Siksika and then a back road to Cluny. From there, we headed south on highway #84, then east on Township Road #194 (where we stopped at the Liberty School site, which will be the subject of a future blog), to an unmarked “road” (more like a path with just two ruts). There was no more signage, for the last 30+ minutes of our journey, but we did have to open three cattle gates. We love a challenge.

FYI: the more popular route is taking the marked route off highway #539 south of the medicine wheel and there is no town of Majorville anymore.

Luckily, Brook’s 4-wheel drive Tundra made for a comfortable ride – and we supposedly saved 3 minutes from the more popular route. The trip confirmed we’d made the right decision in cancelling the trip so many times. We knew the road would be treacherous if wet, there is no cell coverage in some areas, and no farm homes in sight. The only things we saw were one herd of cattle, several orphan wells and endless grasslands.

The route from Highway 539 I better marked than the one from Township Road 194 we took.

We’ve Arrived

This is the entrance gate to the medicine wheel.

There is no grand entrance to the medicine wheel - you just see a large pile of rocks on a modest hill fenced off with a modest information sign. The biggest WOW is the view of the majestic Bow River Valley. Once out of your vehicle, you begin to appreciate the unique sense of place.

A warm chinook wind was blowing, the view from the top of the hill was breath-taking – you could literally see for 100s of kilometers with no sign of human intervention. Even the sky looked different, it has a flatness that I had never seen before.

But, back to the cairn and wheel – ironically, there are very few rocks in the immediate area, so the cairn rocks all had to be dragged there from quite a distance – quite a feat when you realize the makers had no horses, no dogs, nor the invention of the wheel as this the cairn and wheel is estimated to be 4,500 years old. It has been called Canada’s Stonehenge as the wheel is older than Stonehenge. And for that matter, it is also older than the Mayan Pyramid of Chichen Itza and the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Older yes, but to be fair, the pile of stones is no match for the pyramids in scale or engineering, though there is more complexity to the cairn and wheel than meets the eye – more on that later.

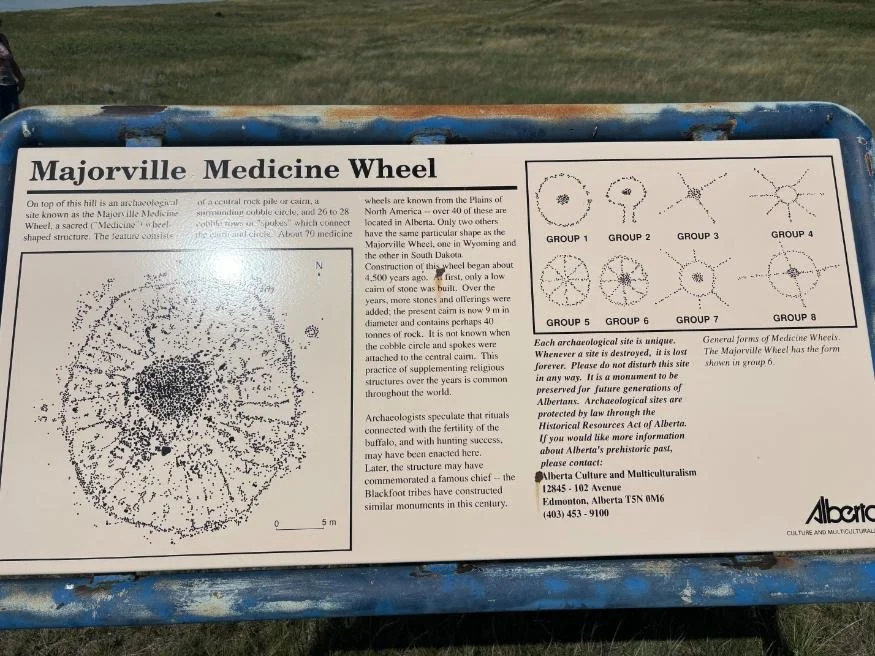

This is the only interpretive information at the site.

The path to the medicine wheel cairn.

You can see for mile and miles and miles from the top of medicine wheel hill, with no evidence of humans anywhere. It is much like the Plains people would have experienced it.

There are lots of offerings tucked into the rocks.

Found this can of tobacco.

We left some blueberries in a box that someone else left at the cairn.

There is a wooden box near the entrance gate with a guest book and other items. We left some feathers.

Looking back you can see our truck and to the right the Bow River.

“What is a medicine wheel?” you ask

According to the Royal Alberta Museum, a medicine wheel consists of at least two of the following three traits: (1) a central stone cairn, (2) one or more concentric stone circles, and/or (3) two or more stone lines radiating outward from a central point. Using this definition, there are a total of 46 medicine wheels in Alberta. Across North America, 8 different types of medicine wheels have been identified.

Majorville Medicine Wheel

From: Canada’s Historic Places (historicplaces.ca)

“The Majorville Cairn and Medicine Wheel is dominated by a 9 m diameter central cairn connected to a 27 m diameter cobble circle by 28 spokes organized in a radially symmetrical fashion and represents one of the most complex designs in existence. It is one of only three known Group 6 medicine wheels in North America.

The rock alignments radiating from the cairn mark the sun rise and set points three days before the spring equinox and three days after the autumn equinox. These days are within two minutes of being exactly 12 hours long as the earth has slightly changed its orientation to the sun over the past 4,500 years. The position of equinox sunrise is marked by a spoke in the Medicine Wheel, which points to a large white limestone rock 61m away, and to a distinct eroded riverbank, 1100m away.”

It is remarkable how they were able to link the medicine wheel to the stars and seasons, thousands of years ago. It is NOT just a random collection of rocks in a symmetrical design.

It is difficult to see the actual wheel from the ground; this photo found online by Greg Olsen via a drone allows you to see the scale of the cairn and wheel.

If you look carefully you can see some of the small rocks radiating from the cairn to the edge of the wheel.

There are several cluster of rocks at the edge of the wheel, that look like they were once smaller cairns.

Buffalo Calling Stones

Majorville Medicine Wheel (also known as Iniskim Umaapi) is a place where Blackfoot ritual activities have taken place for millenniums. Iniskim Umaapi is Blackfoot for “buffalo calling stones.” Standing there, it is easy to imagine tens of thousands of buffalo grazing on the seemingly endless grasslands that surround the cairn and wheel.

As you explore the cairn you will find offerings of sweetgrass, sage, willow, cloth and tobacco, which symbolically maintain the link of the contemporary indigenous people with their ancestors. Be sure to take some time to look at the rocks carefully to see all the offerings people have left. You might even want to bring your own. We brought feathers and blueberries. We were lucky to find a petrified coil of ammonite shell that in Blackfoot Nation folklore ensured the return of the migrating buffaloes.

Archaeological studies indicate this site has been continuously used for the last 4,500 years, making this one of the oldest human site in North America. We also found tipi ring sites located in the undisturbed grassland just east of the fenced off area as we walked towards the Bow River. The site provides an appreciation of the vastness of the prairie grasslands, and the untouched beauty of the Bow River valley.

We couldn’t help but initially wonder why the medicine wheel was in such a remote place, but then you realize that when it was built, all of Alberta was remote, all the world was pretty remote (the total human population was about 50 million then). This high spot on the prairies with its amazing vista would have been attractive to the first people, to spot the bison herds grazing on the lush grassland. The Blackfoot loved the bison as they were their major source of food. The nearby steep cliffs which would have made excellent buffalo jumps. The Blackfoot hunted bison by enticing the herds to stampede in the direction of a steep cliff where they would fall over and die or be injured so they could be easily killed at the base.

Note: If you want to learn more about buffalo jumps, you will have to visit Head Smashed in Buffalo Jump, a UNESCO heritage site, near Fort Mcleod, Alberta.

This painting, 'Buffalo Jump,' by Alfred Jacob Miller, dates from the 19th century, but archeological evidence suggests that Indigenous people executed carefully-planned bison hunts for several thousand years — long before the arrival of Europeans (and before the arrival of the horse)

This is one of three teepee rings we found. You could easily miss them. There are probably hundreds of them hidden in the grassland fields around the Medicine Wheel.

Walk towards the Bow River and you will be rewarded with a stunning view of the Bow River Valley as it winds its way through the prairie grasslands. You will see the steep cliffs that would have made for excellent Buffalo Jumps.

Look back from the Bow River bluff and you see the deep coulees carved by water and wind over millenniums.

Last Word

A visit to the Majorville Medicine Wheel is a walk back in time and a thought-provoking experience. You can’t help but wonder and marvel how the Plains people who wandered these lands endlessly on foot for 1,000s of years following the buffalo herds to survive. The winters must have been horrific.

The cairn, medicine wheel and associated ceremonial area is 20,000 times larger than originally thought and protected by Alberta Government. The public is welcome to visit the site but be respectful.

While you are in the area, you might want to plan to visit the Blackfoot Crossing Museum, and the Treaty Seven cairn, both just south of Cluny. The museum has a copy of the Treaty 7 - a land treaty signed in 1877, the Canadian government and the Blackfoot Confederacy, along with the Stoney-Nakoda and Tsuu T'ina First Nations. In exchange for ceding their traditional territories, the First Nations were promised reserves, education, supplies, and other considerations. However, the government's failure to uphold its promises and the disappearance of bison led to hardship and starvation for the Blackfoot almost immediately after signing. In June 2022,

The Siksika Nation, also known as the Blackfoot, received a $1.3 billion settlement from the Canadian government to resolve a historical land claim. This settlement addresses the wrongful taking of nearly half of the Siksika Nation's reserve land, dating back to 1910. The settlement also includes claims related to the Bow River Irrigation District and the Canadian Pacific Railway.

A view of the endless grasslands of southeastern Alberta. The prairie isn’t as flat as most people think. It has a subtle beauty and softness. Look closely and you will find amazing flowers and lichen painted rocks.

Last Last Word

Brook our driver and lover of the prairies shared, “The Coulees, seem to appear out of nowhere, and at times only visible from certain angles, but upon further investigation they are deeper valleys than anticipated, good places to get out of the wind for animals or people. I love the random boulders in the middle of nowhere, the seasonal wetlands the map says you are crossing, but in reality, it is just a wee dip in the road in late summer. The beauty of the substantial floodplain expanding out from the existing river that meanders through the valley, the bluffs in the distance, with steep slopes and sometimes cliffs formed by erosion are incredible. The deer that spring out of the shaded valley suddenly when they smell our scent off the blowing wind, the enormous amount of different fescue grasses and plants adapted to the dry, windy environment such as the blue grama, June grass, needle and thread and wheatgrass, sagebrush and prickly pear cactus, etc. The subtle beautiful of the prairie reminds me of the quote from an American writer Willa Cathe; “Anyone can love the mountains, but it takes a soul to love the prairies.”

Brook scouting for a bison herd?

A panorama photo of the Bow River Valley at the Majorville Medicine Wheel.